The Cane-Cutter’s Song: Of an escape from ‘kaala paani’, but not misery

Harvinder Khetal ("The Tribune")

The reader is inexorably drawn to turning the pages of this book as the bleak tale of the Indian emigrant cane-cutter, who fled his hometown of Madurai after seeing his poverty-stricken frail parents being devoured by jackals, slowly unfolds. Each incident evocatively paints a picture of that time when the century had turned — 1900.

Striking an empathetic chord is this story of oppressive hardships endured by the god-fearing Dorassamy family from Tamil Nadu, lured into crossing the dreaded ‘kaala paani’ (the Indian and Atlantic oceans) to reach America in the hope of a better life. Instead, they find themselves condemned to the miserable life of indentured labourers in the cane-fields of the never-heard-of French colony of Martinique in the Caribbean.

Adding to the allure of the fictional account of Adhiyaman Dorassamy, his wife Devi and their two sons — each representing a different aspect of those times when economic deprivation drove deep-set cultural mores to the wayside, giving way to the forging of new ties and values — are the factual circumstances around which it is woven. How the autocratic White plantation owners, faced with resistance from Negroes (as the Blacks were then referred to) demanding their right to equality, con and exploit powerless Indian emigrants and their children into the backbreaking job of cutting cane with machetes that left the bodies bruised. And how in a bid to retain some sense of dignified identity, the coolies, as the Indians were derisively labelled, cling to whatever little they know of the Tamil gods and traditions seeped in caste pride and divisions — in secret, lest the iconoclastic Christian authorities trample upon them.

‘The Cane-Cutter’s Song’ is Mumbai University professor Vidya Vencatesan’s translation of the award-winning Martinican author Raphael Confiant’s French book ‘La Panse du Chacal’ (‘The Belly of the Jackal’). Vidya scores a point through her persuasive exploration and vivid depiction peppered with smatterings of Tamil, French and Creole, especially their pithy idioms.

It gives a peek into the lesser-known amalgamation of Indian emigrants with the Creole culture and locals who comprised Blacks, Mulattoes and Whites, their roles in society clearly delineated. How, eventually, only those who come to terms with the fact that their umbilical cord with Madras is cut forever manage to survive, even prosper, while those unable to break free from their roots end up losing their minds.

Like The Ancestor, a revered character in the book, who had dedicated his life to keeping the flame of Tamil language and knowledge of sacred texts burning while pretending to toe the line of the White man, finally, resigns himself to fate. He shuts up voices opposed to Devi cohabiting with a local after Adhiyaman, caught by melancholy on realising that he would never be repatriated to India, wanders away. The Ancestor’s deathbed utterance is an acceptance of the oneness of humanity, even as distinct races remain unique: “There was nothing unhealthy about this union because it was time to kiss the dream of returning to India goodbye. It was time to admit that Martinique had become their country, even if there was no question of forgetting their ancestral gods.”

True, while moving on is the only option for survival, and most Indians are firmly entrenched and prospering in societies their forefathers embraced, it is imperative to not forget the sacrifices made by the early settlers and the collective wisdom of their origins. With immigration and global jet-setting a thing of almost every other family today, such stories give an anchoring perspective to a world undergoing a social and cultural churning at a faster pace than ever.

- Se connecter ou s'inscrire pour publier un commentaire

- 106 vues

Connexion utilisateur

Dans la même rubrique

Top 5 des articles

Aujourd'hui :

- Les "Indiens" d'Oklahoma récupèrent leur territoire ancestral

- Créolité et francophonie: un éloge de la diversalité

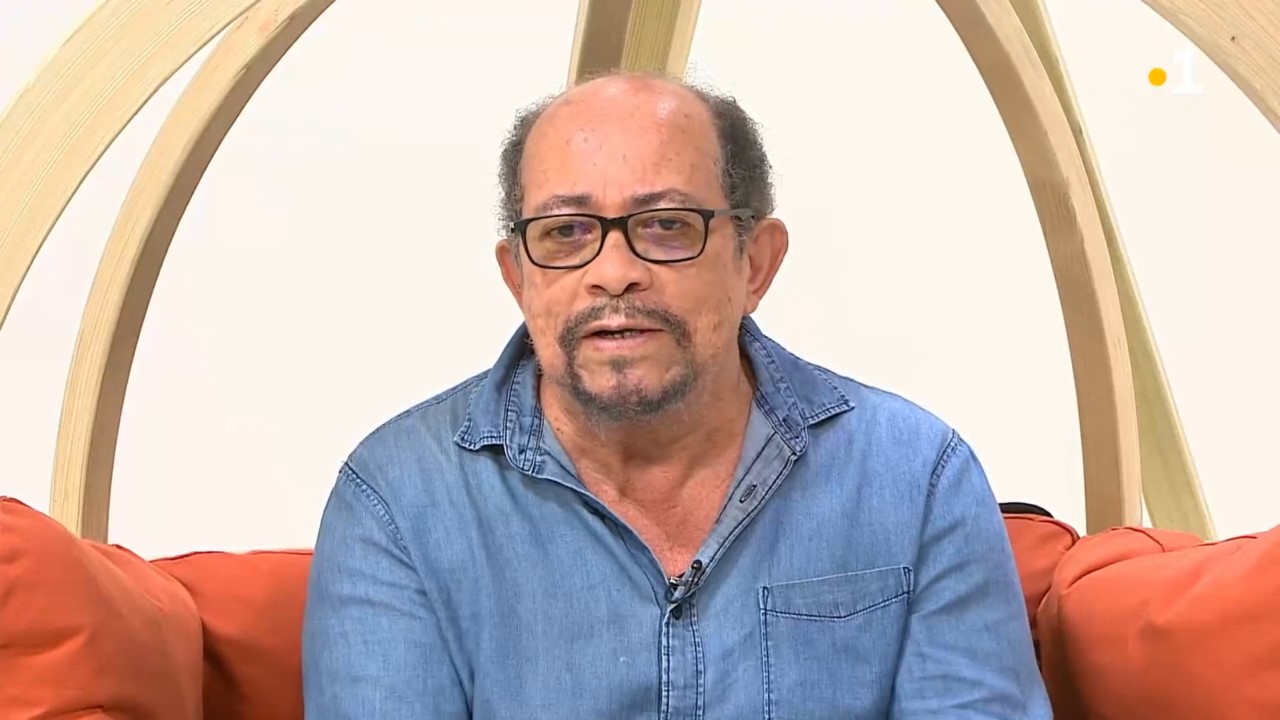

- Raphaël Confiant, écrivain prolifique et citoyen engagé

- Raphaël Confiant: un langage entre attachement et liberté

- Mort de Jacques Coursil, jazzman génial et figure méconnue de la modernité noire

Depuis toujours :

- Le grand livre des proverbes créoles

- Les stupéfiantes facultés divinatoires de Concept Lapierre, voyant du Morne-des-Esses

- LA DIFFERENCE CONCEPTUELLE ENTRE LA NEGRITUDE, L'ANTILLIANITE ET LA CREOLITE

- Raphaël Confiant

- Césaire fut "anté-créole" et pas "anti-créole"

Visiteurs

- Visites : 1231139

- Visiteurs : 89319

- Utilisateurs inscrits : 48

- Articles publiés : 309

- Votre IP : 216.73.216.3

- Depuis : 09/05/2022 - 19:37