Back in the time of harrowing sea crossings

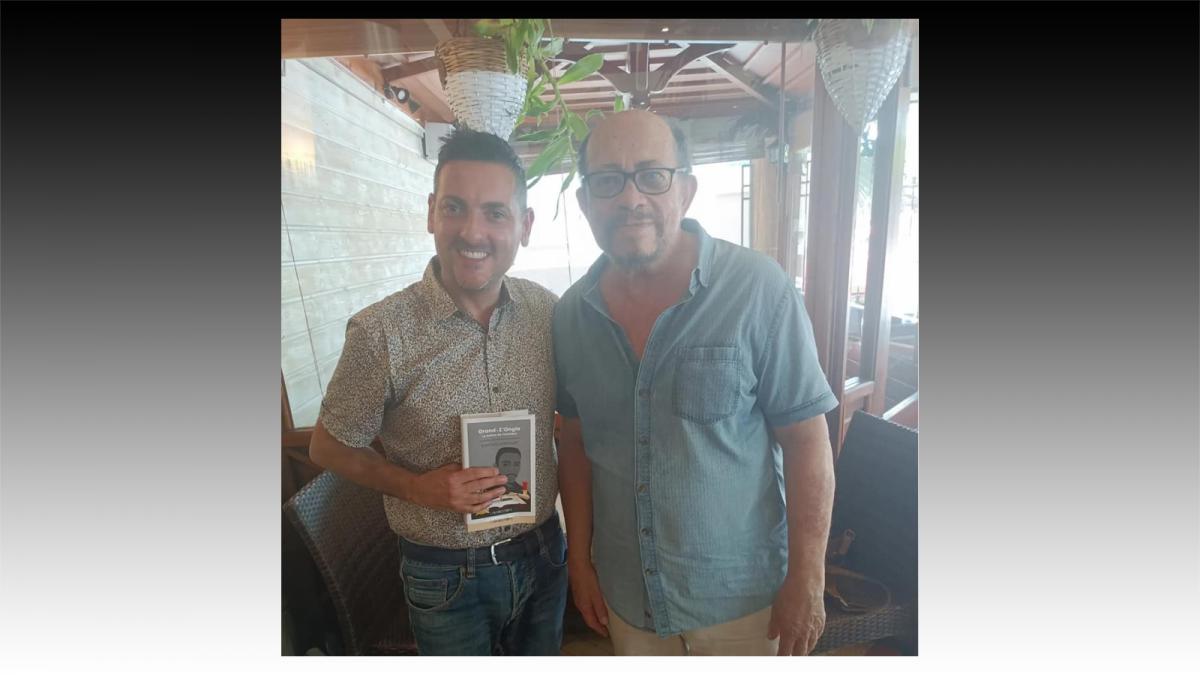

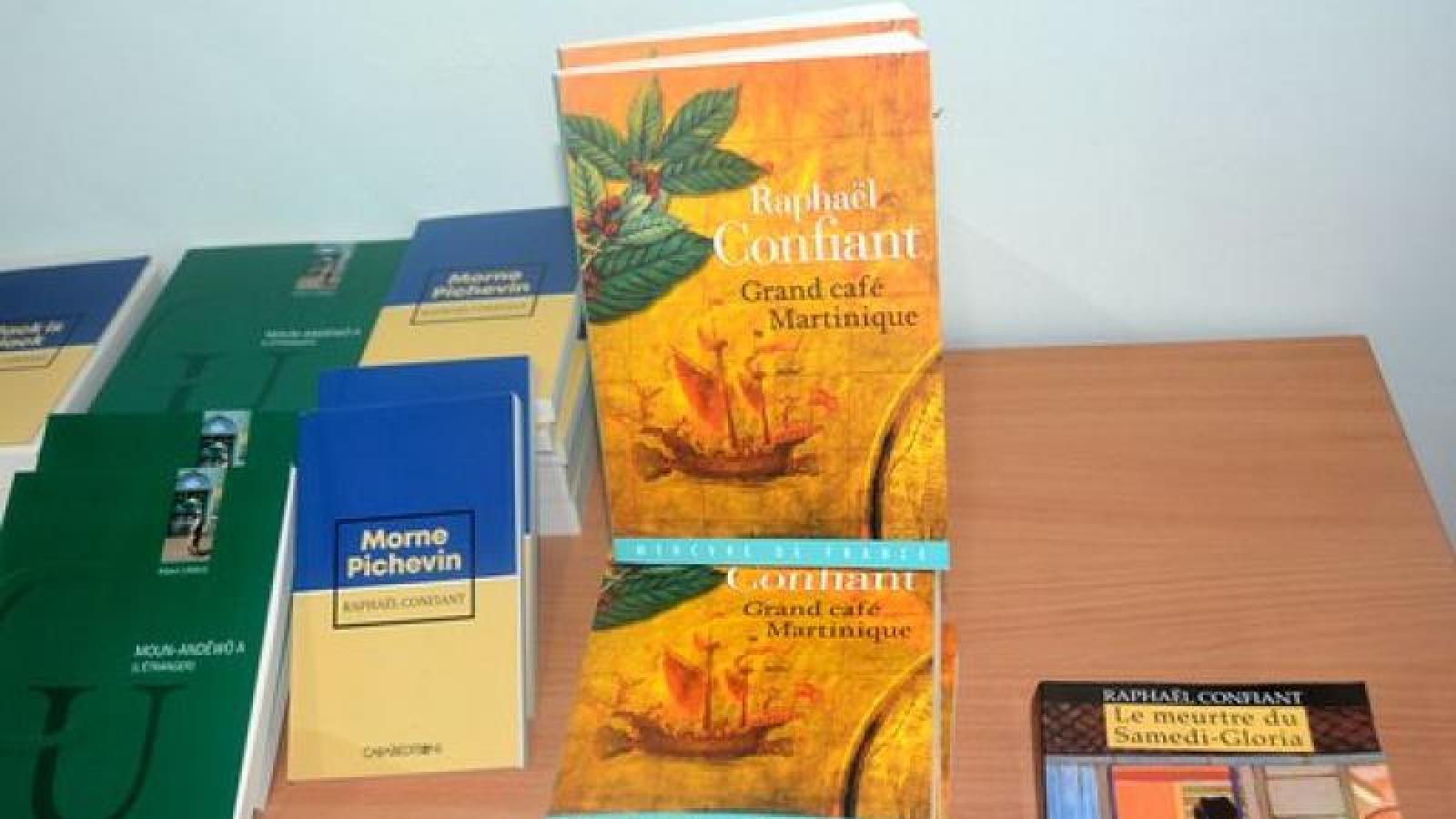

Publié en 2019, le roman "Grand Café Martinique" de Raphaël Confiant, qui nous fait revivre l'épopée de l'introduction du café dans notre île, tout premier endroit du continent américain où il fut planté, a connu un succès certain dans le monde francophone et intéresse maintenant l'anglophone.

Ci-après l'extrait d'un article à son sujet publié par Jeremy Patterson dans The French Review laquelle est éditée par la John Hopkins University Press (USA)...

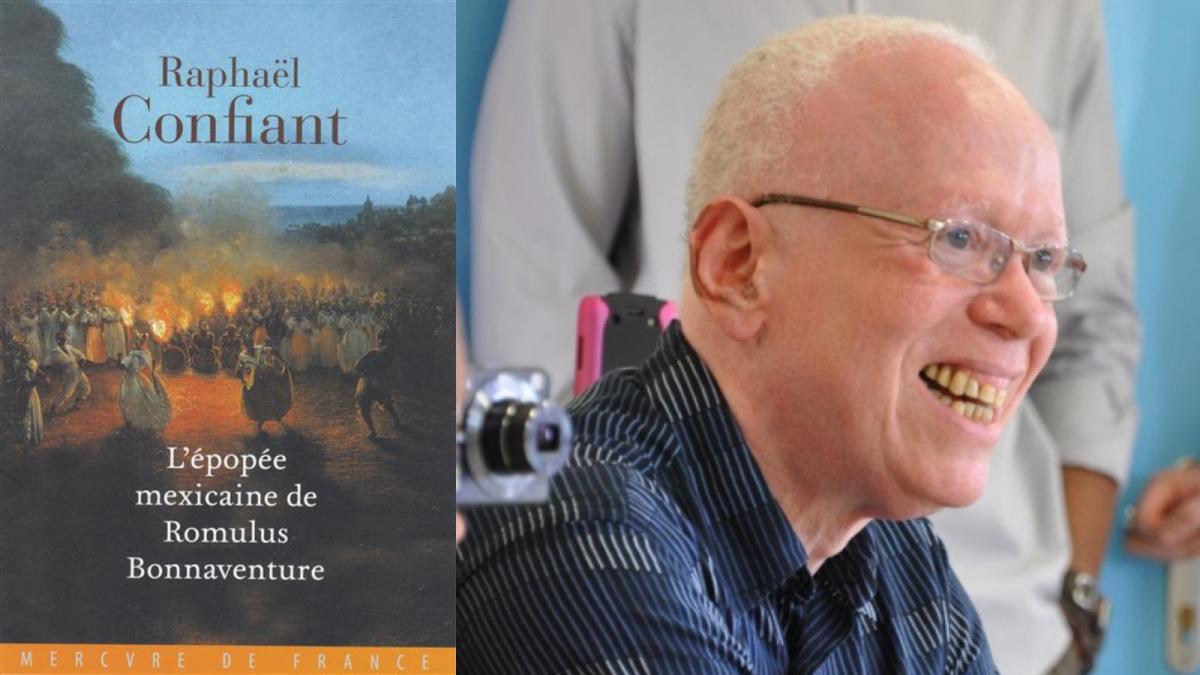

Gabriel-Mathieu d'Erchigny de Clieu is famed for having introduced coffee, or specifically coffee plants, in Martinique. In the 1700s, coffee was one of many plants and products that were making incursions into the European lifestyle and providing [End Page 230] an economic impetus for imperialism and slavery, as Confiant recounts in his latest novel: "Pomme de terre, maïs, cacao, tabac, canne à sucre: les plantes du Nouveau Monde supplantaient peu à peu celles de l'Ancien" (15). In his ongoing project of portraying as much of Martinican society and history as possible in his novels, Confiant has largely focused on events and challenges from the past, building fictional characters around them. On occasion, however, he also takes a historical figure and teases out the story from history around that person. He did so with Stéphanie Saint-Clair, the New York mobster, as his protagonist in Madame St-Clair, reine de Harlem (2015), or with the secondary character of Maximilian I as emperor of Mexico in L'épopée mexicaine de Romulus Bonnaventure (2018). Confiant once again turns to history for his main character in Grand Café Martinique to recount a story that does not at first glance appear to be as tied up with the history of colonialism, imperialism, oppression, and war, compared to many of his other historical novels. The subject of this latest novel, however, provides just as much material for the romancier de l'épopée créole to take readers back in time to harrowing sea crossings, cross-cultural romances, and the political and social domination of the island of Martinique. Confiant also employs several techniques that his readers will recognize. He uses a structure of cercles as he has done in works such as Les Saint-Aubert: les trente-douze mille douleurs 1920–1940 (2014). The five circles gradually get geographically smaller as they trace the life and work of de Clieu until he makes it to Martinique with his coffee plants—no small feat in the eighteenth century, crossing the Atlantic while trying to keep plants alive aboard a vessel. The story begins with de Clieu trying to figure out how he is going to make his name and fortune, moving beyond his hometown of Dieppe, where "de vieux hobereaux qui, tels que mon père, ne s'étaient jamais éloignés de leurs fiefs que de quelques centaines de lieues" (15). But the action was elsewhere, and de Clieu starts out hoping to back his fortune in tobacco. From this first chapter in the first cercle, "J'ai fait un rêve d'Amérique" (1702), de Clieu overcomes missteps, hurricanes, and pirates until finally, in the second-to-last chapter ("Terre! Terre! Terre!") he finally achieves his dream: "Il m'aura été donné d'être le premier homme à avoir transplanté le café aux Amériques. Oui, le tout premier! Et cela demeurera gravé à jamais dans les livres d'histoire" (278). Confiant's genius is here once again on display in turning up and then recounting in novelistic detail so many facets from so many different perspectives of the history and society of the island of Martinique.

Jeremy Patterson

Bob Jones University (SC)

- Se connecter ou s'inscrire pour publier un commentaire

- 15 vues

Connexion utilisateur

Dans la même rubrique

Top 5 des articles

Aujourd'hui :

- Saint-John Perse ou l’antique phrase humaine

- "Le tanbouyé des sans voix" d'Ernest Pépin : une évocation saisissante de Vélo, le grand maître du tambour-ka

- Jeanne Duval, "la muse ténébreuse de Baudelaire" aux identités multiples

- "Grif An Tè" (1979-83), le premier journal martiniquais entièrement en créole

- L'Institut d'Etudes Politiques d'Aix-en-Provence et ses anciens étudiants

Depuis toujours :

- Le grand livre des proverbes créoles

- Les stupéfiantes facultés divinatoires de Concept Lapierre, voyant du Morne-des-Esses

- LA DIFFERENCE CONCEPTUELLE ENTRE LA NEGRITUDE, L'ANTILLIANITE ET LA CREOLITE

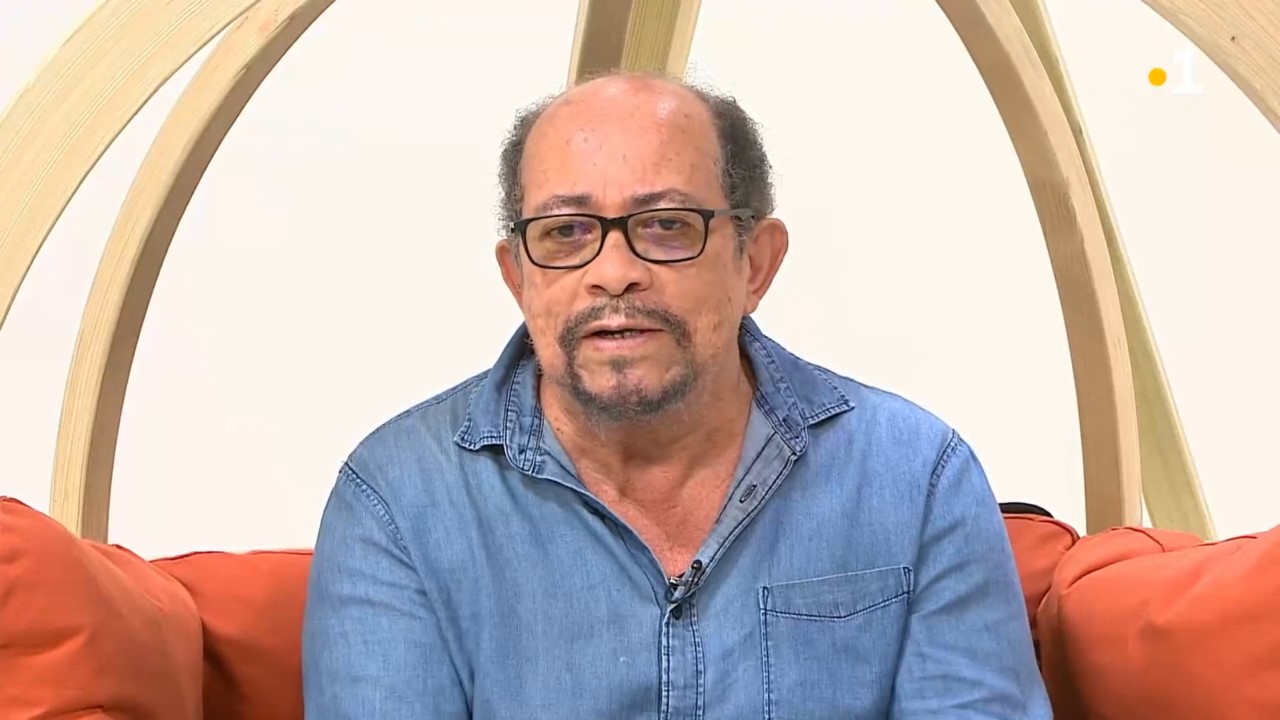

- Raphaël Confiant

- Césaire fut "anté-créole" et pas "anti-créole"

Visiteurs

- Visites : 1229750

- Visiteurs : 89193

- Utilisateurs inscrits : 48

- Articles publiés : 309

- Votre IP : 216.73.216.1

- Depuis : 09/05/2022 - 19:37